The trouble with the word garage is, of course, that there's no acceptable way to say it.

GArridge?

GArahge?

or, in the French way,

gaRARjhe (to rhyme with fromage)?

In these circumstances, any attempt at pronouncing the word is a perilous undertaking.

GArridge is said to be both upper and lower class, and GArahge is said to be middle class.

gaRARghe is strictly for snobs (unless you're French, when it's fine).

To make things worse, even though more or less everyone is now middle class, no one wants to admit it.

So what's the solution?

Well, round here, most people are converting the blasted things into playrooms or kitchens.

Word Not To Use Today: garage. This word comes from French, of course, from garer to dock (a ship) from an Old French word meaning to protect. It's basically the same word as the war- words that are to do with protection, like ward and wardrobe.

f

Sunday, 31 March 2019

Saturday, 30 March 2019

Saturday Rave: Clair de Lune by Paul Verlaine.

Did you know Debussy's Clair de Lune has words?

Well, it does. In fact the words came before the music, and they were written by this man:

who may look like the minor schoolteacher he sometimes was, but he was a passionate man and an uncompromising poet - a poète maudit, or cursed poet, as he called himself.

His name was Paul Verlaine, and he was brave, cowardly, straight, gay, loving, ferocious...but above all a poet. He wrote of dreams, drugs, mysterious forces, veils, fate and feelings, quite deliberately eschewing clarity and strength of argument for suggestion and mist and music. The music of words captivated him.

Here's his poem Clair de Lune.

Well, it does. In fact the words came before the music, and they were written by this man:

who may look like the minor schoolteacher he sometimes was, but he was a passionate man and an uncompromising poet - a poète maudit, or cursed poet, as he called himself.

His name was Paul Verlaine, and he was brave, cowardly, straight, gay, loving, ferocious...but above all a poet. He wrote of dreams, drugs, mysterious forces, veils, fate and feelings, quite deliberately eschewing clarity and strength of argument for suggestion and mist and music. The music of words captivated him.

Here's his poem Clair de Lune.

Votre âme est un paysage choisi

Que vont charmant masques et bergamasques,

Jouant du luth et dansant, et quasi

Tristes sous leurs déguisements fantasques!

Que vont charmant masques et bergamasques,

Jouant du luth et dansant, et quasi

Tristes sous leurs déguisements fantasques!

Tout en chantant sur le mode mineur

L'amour vainqueur et la vie opportune.

Ils n'ont pas l'air de croire à leur Bonheur,

Et leur chanson se mêle au clair de lune,

L'amour vainqueur et la vie opportune.

Ils n'ont pas l'air de croire à leur Bonheur,

Et leur chanson se mêle au clair de lune,

Au calme clair de lune triste et beau,

Qui fait rêver les oiseaux dans les arbres,

Et sangloter d'extase les jets d'eau,

Les grands jets d'eau sveltes parmi les marbres.

Qui fait rêver les oiseaux dans les arbres,

Et sangloter d'extase les jets d'eau,

Les grands jets d'eau sveltes parmi les marbres.

Your soul is a choice landscape

Where charming masked folk and revellers roam

Playing the lute and dancing and seeming almost

Sad under their fantastic disguises.

Playing the lute and dancing and seeming almost

Sad under their fantastic disguises.

Even while singing in a minor key

Of victorious love and good life

They don't seem to believe in their own happiness

And their song mingles with the moonlight,

Of victorious love and good life

They don't seem to believe in their own happiness

And their song mingles with the moonlight,

With the sad and beautiful moonlight,

That makes the birds in the trees dream

And the fountains sob with ecstasy,

The slim fountains among the marble figures.

That makes the birds in the trees dream

And the fountains sob with ecstasy,

The slim fountains among the marble figures.

******

What happens when we ourselves see a moonlit scene?

Perhaps what happens is that we discover if we're really poets.

Word To Use Today: moon. The Old English form of this word was mōna.

Friday, 29 March 2019

Word To Use Today: lipophilicity.

There's a spring in the feet of some words, and a perfect example is the word lipophilicity.

(My British dictionary recommends that the first syllable rhymes with dip, which makes the whole thing particularly elegant: lipophilicity. Isn't it beautiful?)

Lipophilicity is the state of having an affinity for lipids - in other words, something that has lipophilicity really likes fat.

Now, just how obliging a word is that? Not only does the word lipophilicity cause a sentence to ripple like a zephyr ruffling a mountain stream, but it adds a certain dignity to our natural human instinct to stuff ourselves with doughnuts and fried chicken.

I think it might be going to become one of my very favourite words.

Word To Use Today: lipophilicity. The lipo- bit comes from the Greek word lipos, which means fat. The rest is to do with the Greek word philos, which means loving.

(My British dictionary recommends that the first syllable rhymes with dip, which makes the whole thing particularly elegant: lipophilicity. Isn't it beautiful?)

Lipophilicity is the state of having an affinity for lipids - in other words, something that has lipophilicity really likes fat.

Now, just how obliging a word is that? Not only does the word lipophilicity cause a sentence to ripple like a zephyr ruffling a mountain stream, but it adds a certain dignity to our natural human instinct to stuff ourselves with doughnuts and fried chicken.

I think it might be going to become one of my very favourite words.

Word To Use Today: lipophilicity. The lipo- bit comes from the Greek word lipos, which means fat. The rest is to do with the Greek word philos, which means loving.

Thursday, 28 March 2019

The orangutan's lighthouse: a rant.

But what on earth, you will be asking, is the orangutan's lighthouse?

Well, don't ask me.

I was watching TV the other day - The Big Bang Theory, as it happens - and there was an advertisement featuring orangutans in headphones.

I've no idea what the thing was advertising, but then I seldom do. There was a voice-over. It wasn't making much sense, but then I wasn't really listening.

Anyway, at the end of the advertisement, a voice-over said Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.

And I had a blinding flash of revelation, because those, as you'll know, are the last words of To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, a book I have read three times and, indeed, studied for an 'A' Level English exam, without ever having the faintest idea what on earth it was all about.

But all the time it was all to do with orangutans playing on their phones!

!!

I feel a sudden sense of deep peace at finally understanding the book after all these years.

But why on earth did I never manage to work that out for myself?

Word To Use Today: fatigue. This word comes from the Latin fatigāre, to tire.

The advertisement can be seen here:

Well, don't ask me.

I was watching TV the other day - The Big Bang Theory, as it happens - and there was an advertisement featuring orangutans in headphones.

I've no idea what the thing was advertising, but then I seldom do. There was a voice-over. It wasn't making much sense, but then I wasn't really listening.

Anyway, at the end of the advertisement, a voice-over said Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.

And I had a blinding flash of revelation, because those, as you'll know, are the last words of To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, a book I have read three times and, indeed, studied for an 'A' Level English exam, without ever having the faintest idea what on earth it was all about.

But all the time it was all to do with orangutans playing on their phones!

!!

I feel a sudden sense of deep peace at finally understanding the book after all these years.

But why on earth did I never manage to work that out for myself?

Word To Use Today: fatigue. This word comes from the Latin fatigāre, to tire.

As if things weren't difficult enough, a version of the quotation on the Goodreads website has Lily laying down her brush in extreme fatigues - though why the silly woman was wearing extreme fatigues (is that something like a chemical-weapon clean-up suit?) is nearly as baffling as the orangutans.

The advertisement can be seen here:

(I now realise that Audible actually own the rights to many of my own books. So if anyone out there fancies, for instance, a theological comedy thriller read by a complete and utter genius, Christian Rodska, it can be found HERE.)

Wednesday, 27 March 2019

Nuts and Bolts: say what you eat.

Apart from the obvious need for people all over the world to say things like spaghetti bolognese, coq au vin and tom yung kung, how does the food we eat affect the way we speak?

A new study by DE Blasi, S Moran, SR Moisik, P Widmer, D Dediu and B Bickel has discovered that the shape of the human mouth is changed by the type of food that's eaten. And, of course, the shape of the mouth affects the types of sounds it can make.

Now, no one is suggesting that Italians speak Italian because yumming up tiramisu encourages those lovely Italian vowels (though you never know, someone might suggest just that, one day), but there does seem to be some evidence that people who eat tough-to-eat food, notably hunter gatherer communities, have lower and upper teeth that meet at the front.

The rest of us tend to keep our front upper teeth further forward than our lower ones.

The research of these fine academics (see above) has shown that this difference in the structure of the mouth affects spoken language. In particular they've found that the language of hunter-gatherer societies tends to use only a quarter of the number of labiodental sounds - that's v s and f s to you and me - as those of us eating more processed food. It's also been shown that as societies depend more and more on mechanically softened food the incidence of v and f sounds increases - or at least, it does in the Indo-European languages examined in the study.

So I suppose this means that in ancient times people probably didn't eat food at all...

...or, when they did, they probably called it by some other name.

Word To Use Today: one beginning with a labiodental sound. Like vanilla or venison or French fries or fettuccine, perhaps.

A new study by DE Blasi, S Moran, SR Moisik, P Widmer, D Dediu and B Bickel has discovered that the shape of the human mouth is changed by the type of food that's eaten. And, of course, the shape of the mouth affects the types of sounds it can make.

Now, no one is suggesting that Italians speak Italian because yumming up tiramisu encourages those lovely Italian vowels (though you never know, someone might suggest just that, one day), but there does seem to be some evidence that people who eat tough-to-eat food, notably hunter gatherer communities, have lower and upper teeth that meet at the front.

The rest of us tend to keep our front upper teeth further forward than our lower ones.

The research of these fine academics (see above) has shown that this difference in the structure of the mouth affects spoken language. In particular they've found that the language of hunter-gatherer societies tends to use only a quarter of the number of labiodental sounds - that's v s and f s to you and me - as those of us eating more processed food. It's also been shown that as societies depend more and more on mechanically softened food the incidence of v and f sounds increases - or at least, it does in the Indo-European languages examined in the study.

So I suppose this means that in ancient times people probably didn't eat food at all...

...or, when they did, they probably called it by some other name.

Word To Use Today: one beginning with a labiodental sound. Like vanilla or venison or French fries or fettuccine, perhaps.

Tuesday, 26 March 2019

Thing To Do Today: bustle.

I wonder why bustling is such a feminine thing?

(I usually write a small exploration of the issue, here, but in this case I don't dare.)

(I've put this photograph in for fun, even though this sort of a bustle is a completely different word from the one we're thinking about.)

Thing To Do Today: bustle. This word appeared in the 1500s. perhaps from buskle, which meant to make energetic preparation, from the Old Norse būask to prepare.

I suppose the masculine equivalent is hustle, isn't it?

This is possibly an even scarier thing to think about in print, so I think I'll shut up.

The origin of the padded-bottom sort of bustle is, sadly, an eighteenth century mystery.

(I usually write a small exploration of the issue, here, but in this case I don't dare.)

(I've put this photograph in for fun, even though this sort of a bustle is a completely different word from the one we're thinking about.)

Thing To Do Today: bustle. This word appeared in the 1500s. perhaps from buskle, which meant to make energetic preparation, from the Old Norse būask to prepare.

I suppose the masculine equivalent is hustle, isn't it?

This is possibly an even scarier thing to think about in print, so I think I'll shut up.

The origin of the padded-bottom sort of bustle is, sadly, an eighteenth century mystery.

Monday, 25 March 2019

Spot the Frippet: buta.

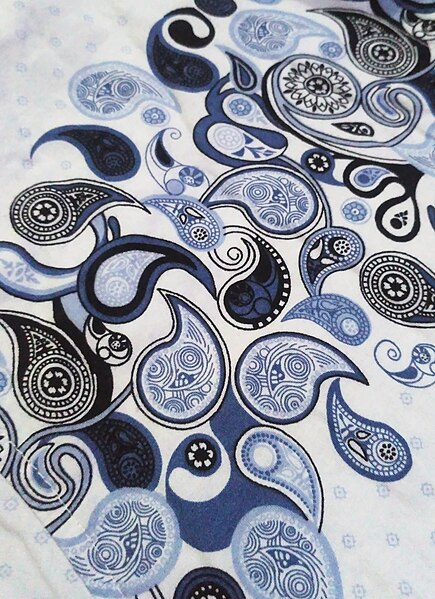

These are butas:

photo by Sialkgraph of a design by Master Reza Vafa Kashani, 1939

Yes, those droopy drop-shaped things.

A design that uses them is often referred to vaguely as paisley-pattern, and it's to be found on fabrics all over the place:

2009 fabric by Hawes and Curtis. Photo by XmgTunis

If you have a tie from the 1960s featuring them then it was probably inspired by the Beatles.

The shapes are thought to be partly inspired by sprays of flowers, and partly by a bending-down cypress tree, a Zoroastrian symbol representing strength and resistance but at the same time modesty.

Butas can be found on carpets, shawls, clothes:

This is from another remarkable shirt. Photo by Gunarta

French doll, circa 1855

and on curtains, paintings and architecture. Azerbaijan even put them on the trousers of their 2010 Winter Olympic team.

In the Baltic States in the 1700s the buta was used to ward-off evil.

Hmm...

...well, I suppose it might be worth a try, mightn't it...

...though not if it involves anyone wearing one of those shirts.

Spot the Frippet: buta. This is a Persian word. It's called paisley pattern because a lot of buta-patterned fabric used to be made in the Scottish town of Paisley.

Sunday, 24 March 2019

Sunday Rest: borecore. Word Not To Use Today.

Look, being a teenager is quite hard enough without people dismissing your six second video of you painting your nails or pretending to be Paddington Bear as borecore.

After all, it's not as if you're not going to grow out of that sort of thing. I mean, before you can work out what's happened you'll be a sixty-year-old banging on about completely different boring things like word-usage...

...whoops…

Word Not To Use Today: borecore. This word originally seems to have been associated with Vine, a deceased Social Media platform which allowed people to make home made six second looping videos publicly available.

Sadly, the videos turned out, though short, to be so reliably boring that almost no one watched them.

The word bore meaning to be uninteresting appeared in the 1700s, but at the time no one was quite interested enough to write down who made it up, and so now the origin of the word is a mystery. The word core, meaning the centre of a structure, appeared in the 1300s. No one knows where that word came from, either, but by the 1800s hard core in Britain meant rubble, especially used to describe the foundations of buildings. Whether this led by some route to hardcore meaning extreme, ie too extreme to shift, is unprovable at the moment, but not unlikely.

After all, it's not as if you're not going to grow out of that sort of thing. I mean, before you can work out what's happened you'll be a sixty-year-old banging on about completely different boring things like word-usage...

...whoops…

Word Not To Use Today: borecore. This word originally seems to have been associated with Vine, a deceased Social Media platform which allowed people to make home made six second looping videos publicly available.

Sadly, the videos turned out, though short, to be so reliably boring that almost no one watched them.

The word bore meaning to be uninteresting appeared in the 1700s, but at the time no one was quite interested enough to write down who made it up, and so now the origin of the word is a mystery. The word core, meaning the centre of a structure, appeared in the 1300s. No one knows where that word came from, either, but by the 1800s hard core in Britain meant rubble, especially used to describe the foundations of buildings. Whether this led by some route to hardcore meaning extreme, ie too extreme to shift, is unprovable at the moment, but not unlikely.

Saturday, 23 March 2019

Akhtamar by Hovhannes Toumanian

Here's a proper story by the Armenian poet Hovhannes Toumanian (1869 - 1923), peace-maker and national poet of Armenia.

Beside the laughing lake of Van

A little hamlet lies

Each night into the waves a man

Leaps under darkened skies.

He cleaves the waves with mighty arm,

Needing no raft or boat,

And swims, disdaining risk and harm,

Towards the isle remote.

On the dark island burns so bright

A piercing, luring ray:

There's lit a beacon every night

To guide him on his way.

Upon the island is that fire

Lit by Tamar the fair,

Who waits, all burning with desire,

Beneath the shelter there.

The lover's heart - how it does beat!

How beat the roaring waves!

But, bold and scorning to retreat,

The elements he braves.

And now Tamar the fair doth hear,

With trembling heart aflame,

The water splashing - oh, so near,

And fire consumes her frame.

All quiet is on the shore around,

And, black there looms a shade:

The darkness utters not a sound,

The swimmer finds the maid.

The tide-waves ripple, lisp and splash

And murmur, soft and low;

The urge each other, mingle, clash

As, ebbing, out they go.

Flutter and rustle the dark waves

And with them every star

Whipers how sinfully behaves

The shamleless maid Tamar

Their whisper shakes her throbbing heart

This time, as was before!

The youth into the waves does dart,

The maiden prays on shore.

But certain villains, full of spite,

Against them did conspire,

And on a hellish, mirky night

Put out the guiding fire.

The luckless lover lost his way,

And only from afar

The wind is carrying in his sway

The moans of 'Ah, Tamar!'

The through the night his voice is heard

Upon the craggy shores,

And, though it's muffled and blurred

By the waves' rapid roars,

The words fly forward - faint they are -

'Ah Tamar!

And in the morn the splashing tide

The hapless youth cast out,

Who, battling with the waters, died

In an unequal bout;

Cold lips are clenched, two words they bar:

'Ah, Tamar!'

And ever since, both near and far,

They call the island Akhtamar.

Well, it was never going to end well, was it?

Tamar, on Akdamar Island by sculptor Rafael Petrosyan.

Word To Use Today: maid. This word comes from the Old English mæden. Entertainingly, it's not only related to the Old Norse mogr, young man, but the Old Irish mug, which means slave.

Beside the laughing lake of Van

A little hamlet lies

Each night into the waves a man

Leaps under darkened skies.

He cleaves the waves with mighty arm,

Needing no raft or boat,

And swims, disdaining risk and harm,

Towards the isle remote.

On the dark island burns so bright

A piercing, luring ray:

There's lit a beacon every night

To guide him on his way.

Upon the island is that fire

Lit by Tamar the fair,

Who waits, all burning with desire,

Beneath the shelter there.

The lover's heart - how it does beat!

How beat the roaring waves!

But, bold and scorning to retreat,

The elements he braves.

And now Tamar the fair doth hear,

With trembling heart aflame,

The water splashing - oh, so near,

And fire consumes her frame.

All quiet is on the shore around,

And, black there looms a shade:

The darkness utters not a sound,

The swimmer finds the maid.

The tide-waves ripple, lisp and splash

And murmur, soft and low;

The urge each other, mingle, clash

As, ebbing, out they go.

Flutter and rustle the dark waves

And with them every star

Whipers how sinfully behaves

The shamleless maid Tamar

Their whisper shakes her throbbing heart

This time, as was before!

The youth into the waves does dart,

The maiden prays on shore.

But certain villains, full of spite,

Against them did conspire,

And on a hellish, mirky night

Put out the guiding fire.

The luckless lover lost his way,

And only from afar

The wind is carrying in his sway

The moans of 'Ah, Tamar!'

The through the night his voice is heard

Upon the craggy shores,

And, though it's muffled and blurred

By the waves' rapid roars,

The words fly forward - faint they are -

'Ah Tamar!

And in the morn the splashing tide

The hapless youth cast out,

Who, battling with the waters, died

In an unequal bout;

Cold lips are clenched, two words they bar:

'Ah, Tamar!'

And ever since, both near and far,

They call the island Akhtamar.

Well, it was never going to end well, was it?

Tamar, on Akdamar Island by sculptor Rafael Petrosyan.

Word To Use Today: maid. This word comes from the Old English mæden. Entertainingly, it's not only related to the Old Norse mogr, young man, but the Old Irish mug, which means slave.

Friday, 22 March 2019

Word To Use Today: fabaceous.

If something is fab is it wonderful, terrific, and amazingly marvellous.

If something is fabaceous, however, it's to do with beans.

It's a distinction worth bearing in mind.

Word To Use Today: fabaceous. This word comes from the Latin faba, which means bean. Fabaceous also covers things to do with peas, gorse, acacia and carob - anything with pods and nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots.

Fab is, of course, short for fabulous. The idea is that something fab is so good it's celebrated in fables.

If something is fabaceous, however, it's to do with beans.

It's a distinction worth bearing in mind.

Word To Use Today: fabaceous. This word comes from the Latin faba, which means bean. Fabaceous also covers things to do with peas, gorse, acacia and carob - anything with pods and nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots.

Fab is, of course, short for fabulous. The idea is that something fab is so good it's celebrated in fables.

Thursday, 21 March 2019

Against Voltaire: a rant.

Evelyn Beatrice Hall, who wrote under the name S G Tallentyre, came up with the line 'I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it'.

Yes, that's right, it's usually attributed to Voltaire, but this is fair enough, really, because that quotation is Hall's summing up of Voltaire's attitude to free speech. It appears in her 1906 book The Friends of Voltaire.

I think that most of us will agree with the sentiment.

I do wish, however, there was some equally famous line which says:

I approve of what you think, but for heaven's sake keep quiet about it until we get home.

It would make get-togethers of friends, family, and work mates so much easier, wouldn't it.

Word To Use Today: approve. This word comes from the Latin probāre to test.

Yes, that's right, it's usually attributed to Voltaire, but this is fair enough, really, because that quotation is Hall's summing up of Voltaire's attitude to free speech. It appears in her 1906 book The Friends of Voltaire.

I think that most of us will agree with the sentiment.

I do wish, however, there was some equally famous line which says:

I approve of what you think, but for heaven's sake keep quiet about it until we get home.

It would make get-togethers of friends, family, and work mates so much easier, wouldn't it.

Word To Use Today: approve. This word comes from the Latin probāre to test.

Wednesday, 20 March 2019

Nuts and Bolts: Zipf's Law.

Zipf's Law of Abbreviation we've already looked at and admired, but how about the other Zipf's Law? The one, that is, that's simply called Zipf's Law?

George Kingsley Zipf was a great man. He was such a great man, indeed, that he resisted any temptation to claim to have made up Zipf's Law himself (as it happens, the French stenographer Jean-Baptiste Estoup seems to have got there first, and the German physicist Felix Auerbach seems have been second. But, hey, it was Zipf who did the publicity, wasn't it?).

Zipf's Law works for quite a few different things, but for our purposes the main idea is that the most common word in a (substantial) text will be twice as common as the next most common word, and three times more common than the next commonest word after that, and so on.

The commonest word in the English language is, unsurprisingly the.

Zipf's Law seems to work for all languages, and no one has come up with a theory that's been generally accepted as to why languages are constructed in that way. It might be partly that the commoner a word is the more likely other people are to choose to use it; but no one really knows.

The question you will be asking is, of course, what's the second commonest word in the English language?

Well, it's be, and then, in order, to, of and and.

The commonest noun (not counting pronouns, and not counting the word make, which is often a verb) is...can you guess?*

A list of the one hundred commonest words in the English language can be found HERE.

Word To Use Today. Well, why not see how long you go without using the word the? The Old English form of this word was thē.

*It's people, which comes in at about number sixty one.

George Kingsley Zipf was a great man. He was such a great man, indeed, that he resisted any temptation to claim to have made up Zipf's Law himself (as it happens, the French stenographer Jean-Baptiste Estoup seems to have got there first, and the German physicist Felix Auerbach seems have been second. But, hey, it was Zipf who did the publicity, wasn't it?).

Zipf's Law works for quite a few different things, but for our purposes the main idea is that the most common word in a (substantial) text will be twice as common as the next most common word, and three times more common than the next commonest word after that, and so on.

The commonest word in the English language is, unsurprisingly the.

Zipf's Law seems to work for all languages, and no one has come up with a theory that's been generally accepted as to why languages are constructed in that way. It might be partly that the commoner a word is the more likely other people are to choose to use it; but no one really knows.

The question you will be asking is, of course, what's the second commonest word in the English language?

Well, it's be, and then, in order, to, of and and.

The commonest noun (not counting pronouns, and not counting the word make, which is often a verb) is...can you guess?*

A list of the one hundred commonest words in the English language can be found HERE.

Word To Use Today. Well, why not see how long you go without using the word the? The Old English form of this word was thē.

*It's people, which comes in at about number sixty one.

Tuesday, 19 March 2019

Thing To Be Today: as pleased as Punch.

To be as pleased as punch is to be thrilled to bits, to be utterly gleeful, to be completely delighted.

It's just a slight shame that the Punch in question is a serial murderer.

Still, never mind, he's a serial murderer designed to amuse small children. So that's all right, then.

Errr...

Here he is, in case you've never come across him:

For the information of those too busy to watch, I'm afraid the reason Punch is so pleased (That's the way to do it! he squawks) is generally that's he's killed another of his victims with his club.

Still, as I say, small children love him.

For anyone to be as pleased as punch something surprisingly wonderful must have happened, so I'm afraid it's not something that can be planned.

Still, we can all hope, can't we.

And look out for delightful things:

Word To Use Today: punch. Punch started off as the puppet Polichinello in the sixteenth century Italian commedia dell'arte. Usually the phrase as pleased as punch no longer uses a capital letter, perhaps because few of us want to associate ourselves too closely with serial murderers.

Even though this obscures the history of the phrase, this is almost certainly a good thing.

The Latin word pullus , which forms the basis of the name Polichinello, means a young animal.

It's just a slight shame that the Punch in question is a serial murderer.

Still, never mind, he's a serial murderer designed to amuse small children. So that's all right, then.

Errr...

Here he is, in case you've never come across him:

For the information of those too busy to watch, I'm afraid the reason Punch is so pleased (That's the way to do it! he squawks) is generally that's he's killed another of his victims with his club.

Still, as I say, small children love him.

For anyone to be as pleased as punch something surprisingly wonderful must have happened, so I'm afraid it's not something that can be planned.

Still, we can all hope, can't we.

And look out for delightful things:

Word To Use Today: punch. Punch started off as the puppet Polichinello in the sixteenth century Italian commedia dell'arte. Usually the phrase as pleased as punch no longer uses a capital letter, perhaps because few of us want to associate ourselves too closely with serial murderers.

Even though this obscures the history of the phrase, this is almost certainly a good thing.

The Latin word pullus , which forms the basis of the name Polichinello, means a young animal.

Monday, 18 March 2019

Spot the Frippet: the readies.

Have you got the readies?

Probably not, nowadays, because most of us are using cards instead of real money - and to make things even worse the cards aren't even made of card, but plastic.

It may be convenient, but think: what is a miser to do?

Or the tooth fairy?

Money has been round longer than there have been any history books to record it. It probably started off with clay tokens issued by warehouses in China, India, Babylon or Egypt, but the idea of money didn't spread steadily around the globe. The trouble is that money depends upon there being someone you trust to issue the stuff - and that isn't a given even nowadays, as can be seen with the rapidly increasing worthlessness of the currencies of countries such as Zimbabwe and Venezuela.

If you do have someone trustworthy in charge, then what is likely to happen about money is this: you start off by giving someone a block of something valuable, like metal, in exchange for goods. The block of metal gives you a bad back, and so the trustworthy person in charge puts his mark on smaller pieces of metal and tells everyone that counts just the same as a bigger bit. Everyone is dubious, but they're all fed up with having bad backs and so they try it out, and on the whole people find it works.

What the money has looked like has varied over the years. There were cowrie shells, of course, and, later, bronze copies of cowrie shells. There has even been money in the shape of small spades; but in the end the bad-temper of the people who had to mend people's worn-out pockets tended to encourage coins to be made as small flat discs.

It's been lovely to carry small but exquisite works of art around with us for thousands of years:

British crown (quarter of a pound sterling) photo by Jerry 'Woody'

Ah well. Perhaps soon our plastic cards might start being beautiful.

And, really, why shouldn't they be round, as well, and made of something precious?

Spot the Frippet: the readies. This is short for ready money. The Old English form of the word ready was rǣde.

Probably not, nowadays, because most of us are using cards instead of real money - and to make things even worse the cards aren't even made of card, but plastic.

It may be convenient, but think: what is a miser to do?

Or the tooth fairy?

Money has been round longer than there have been any history books to record it. It probably started off with clay tokens issued by warehouses in China, India, Babylon or Egypt, but the idea of money didn't spread steadily around the globe. The trouble is that money depends upon there being someone you trust to issue the stuff - and that isn't a given even nowadays, as can be seen with the rapidly increasing worthlessness of the currencies of countries such as Zimbabwe and Venezuela.

If you do have someone trustworthy in charge, then what is likely to happen about money is this: you start off by giving someone a block of something valuable, like metal, in exchange for goods. The block of metal gives you a bad back, and so the trustworthy person in charge puts his mark on smaller pieces of metal and tells everyone that counts just the same as a bigger bit. Everyone is dubious, but they're all fed up with having bad backs and so they try it out, and on the whole people find it works.

What the money has looked like has varied over the years. There were cowrie shells, of course, and, later, bronze copies of cowrie shells. There has even been money in the shape of small spades; but in the end the bad-temper of the people who had to mend people's worn-out pockets tended to encourage coins to be made as small flat discs.

It's been lovely to carry small but exquisite works of art around with us for thousands of years:

British crown (quarter of a pound sterling) photo by Jerry 'Woody'

Ah well. Perhaps soon our plastic cards might start being beautiful.

And, really, why shouldn't they be round, as well, and made of something precious?

Spot the Frippet: the readies. This is short for ready money. The Old English form of the word ready was rǣde.

Sunday, 17 March 2019

Sunday Rest: mutule. Word Not To Use Today.

This horrid word is all the more annoying for having a vastly unhelpful dictionary definition: one of a set of flat blocks below the corona of a Doric cornice.

Did you understand that? I was fine until the words started having more than one syllable - but it's all right, I've done the research so you don't have to.

A corona (in architecture) is the flat vertical face of a cornice just above the soffit. And a soffit is...

...oh, blow this for a lark. Let's find an illustration.

1. Tympanum, 2. Acroterion, 3. Sima, 4. Cornice, 5. Mutule, 7. Frieze, 8. Triglyph, 9. Metope, 10. Regula, 11. Gutta, 12. Taenia, 13. Architrave, 14. Capital, 15. Abacus, 16. Echinus, 17. Column, 18. Fluting, 19. Stylobate

Illustration by Napoleon Vier.

So there we are. There's a mutule at Number 5. The corona, in case you're wondering, is the lower piece of the cornice.

A mutule still sounds like something you'd find in a far paragraph of an insurance contract, or else something lurking in some deep crevice of the human anatomy, though, doesn't it.

(And it doesn't look that much like a flat block, either.)

Word Not To Use Today: mutule. This word comes from the Latin word mūtulus, which means modillion...

...oh all right, I suppose I'll have to look that up, now!...

A modillion is a thing holding up a cornice. Here are a row of them.

But if they're less chunky they're called dentils, apparently.

Anyone out there still got the will to live?

Did you understand that? I was fine until the words started having more than one syllable - but it's all right, I've done the research so you don't have to.

A corona (in architecture) is the flat vertical face of a cornice just above the soffit. And a soffit is...

...oh, blow this for a lark. Let's find an illustration.

1. Tympanum, 2. Acroterion, 3. Sima, 4. Cornice, 5. Mutule, 7. Frieze, 8. Triglyph, 9. Metope, 10. Regula, 11. Gutta, 12. Taenia, 13. Architrave, 14. Capital, 15. Abacus, 16. Echinus, 17. Column, 18. Fluting, 19. Stylobate

Illustration by Napoleon Vier.

So there we are. There's a mutule at Number 5. The corona, in case you're wondering, is the lower piece of the cornice.

A mutule still sounds like something you'd find in a far paragraph of an insurance contract, or else something lurking in some deep crevice of the human anatomy, though, doesn't it.

(And it doesn't look that much like a flat block, either.)

Word Not To Use Today: mutule. This word comes from the Latin word mūtulus, which means modillion...

...oh all right, I suppose I'll have to look that up, now!...

A modillion is a thing holding up a cornice. Here are a row of them.

But if they're less chunky they're called dentils, apparently.

Anyone out there still got the will to live?

Saturday, 16 March 2019

Saturday Rave: Ach, wie nichtig by Michael Franck

Michael Franck was born in Schleusingen, in Thuringia, Germany, in 1609. He was a baker.

He seems to have been quite a good baker, though sadly he wasn't much cop at the business side of things: basically, he never found a way to stop people breaking in at night and nicking his stuff. In the end, completely broke, he abandoned his business and started up a new line as a teacher, with a bit of poetry thrown in as a side-line.

Perhaps surprisingly, the poetry was fairly successful, and his verses were set to music by both J S Bach and Telemann.

Here is some of Franck's poem Ach wie flüchtig,

ach wie nichtig which Bach used in his 1724 Church Cantata BMV 26.

Ach wie flüchtig,

ach wie nichtig

ist des Menschen Leben!

Wie Ein NEBEL bald enstehet

und ach wie der bald vergehet

so ist unser LEBEN sehet!

Ach wir nichtig,

ach wie flüchtig

sind der Menschen Sachen!

Alles, alles was wir sehen,

das muß fallen und vergehen,

Wer Gott fürcht', wird ewig stehen.

**

Ah, how fleeting,

ah how insubstantial

is man's life!

As a mist soon arises

and soon also vanishes again,

so is our life, see!

Ah, how insubstantial,

ah how fleeting

are mankind's affairs!

Ah, all that we see

must fall and vanish.

The person who fears God stands

firm forever.

Word To Use Today: fleeting. Ironically, no one is sure of the derivation of this word. It might be something to do with the Old English flēotan, to float or glide rapidly and before that to the Latin pluere, to rain.

The rest of this wistful but lovely poem (these are just the first and last verses) can be found HERE.

He seems to have been quite a good baker, though sadly he wasn't much cop at the business side of things: basically, he never found a way to stop people breaking in at night and nicking his stuff. In the end, completely broke, he abandoned his business and started up a new line as a teacher, with a bit of poetry thrown in as a side-line.

Perhaps surprisingly, the poetry was fairly successful, and his verses were set to music by both J S Bach and Telemann.

Here is some of Franck's poem Ach wie flüchtig,

ach wie nichtig which Bach used in his 1724 Church Cantata BMV 26.

Ach wie flüchtig,

ach wie nichtig

ist des Menschen Leben!

Wie Ein NEBEL bald enstehet

und ach wie der bald vergehet

so ist unser LEBEN sehet!

Ach wir nichtig,

ach wie flüchtig

sind der Menschen Sachen!

Alles, alles was wir sehen,

das muß fallen und vergehen,

Wer Gott fürcht', wird ewig stehen.

**

Ah, how fleeting,

ah how insubstantial

is man's life!

As a mist soon arises

and soon also vanishes again,

so is our life, see!

Ah, how insubstantial,

ah how fleeting

are mankind's affairs!

Ah, all that we see

must fall and vanish.

The person who fears God stands

firm forever.

Word To Use Today: fleeting. Ironically, no one is sure of the derivation of this word. It might be something to do with the Old English flēotan, to float or glide rapidly and before that to the Latin pluere, to rain.

The rest of this wistful but lovely poem (these are just the first and last verses) can be found HERE.

Friday, 15 March 2019

Word To Use Today: walnut.

Walnuts don't grow on walls:

photo of a walnut tree by JLPC

so what's that all about?

This:

Word To Use Today: walnut. The Old English form of this word is the charming wahl-hnutu, which means foreign nut. The Old French (that is, the language spoken in France before its inhabitants got so polished and eternally youthful) form of the word was noux gauge, which probably comes from the Latin nux gallica, or Gaulish nut. This implies foreign, too.

photo of unripe walnuts by George Chernilevsky The French tend to pickle their walnuts at this stage. They're delicious.

So where do walnuts actually come from? The two commonest types are the English walnut, Juglans regia:

illustration by Amédée Masclef

which comes, obviously, from Iran, and the black walnut, Juglans nigra, which comes from the eastern parts of North America. The sort commercially available are of the English type because the black walnut, though tasty, has a very hard shell which means it's hard to get the meaty bit out in one piece.

Final fact: the brown skin on the surface of a walnut kernel is full of stuff that stops the nut inside going off.

photo of a walnut tree by JLPC

so what's that all about?

This:

Word To Use Today: walnut. The Old English form of this word is the charming wahl-hnutu, which means foreign nut. The Old French (that is, the language spoken in France before its inhabitants got so polished and eternally youthful) form of the word was noux gauge, which probably comes from the Latin nux gallica, or Gaulish nut. This implies foreign, too.

photo of unripe walnuts by George Chernilevsky The French tend to pickle their walnuts at this stage. They're delicious.

So where do walnuts actually come from? The two commonest types are the English walnut, Juglans regia:

illustration by Amédée Masclef

which comes, obviously, from Iran, and the black walnut, Juglans nigra, which comes from the eastern parts of North America. The sort commercially available are of the English type because the black walnut, though tasty, has a very hard shell which means it's hard to get the meaty bit out in one piece.

Final fact: the brown skin on the surface of a walnut kernel is full of stuff that stops the nut inside going off.

Thursday, 14 March 2019

Mr Smith's centre ground: a rant.

Today's rant was written by Mr J Alan Smith, of Epping, Essex, England, and published as a letter in the Telegraph newspaper.

It's about labels - and how they so often end up stuck over the flipping bar code.

SIR - The political affection for the "centre ground" and the disdain for "extremes", the "far-Right" and - very occasionally - the "far-Left" rest on the assumption that each of us can be represented by points on a line according to our political views.

Suppose that this is not true. We should have to replace the "centre ground" with the more useful "common ground" and, instead of debating whether proposals were of the Right or Left, debate whether the were right or wrong.

J Alan Smith

Epping, Essex

How about that? Sorts out the world in three sentences!

Word To Us Today: right. Both the main meanings of this word, correct and the opposite of left, have the same origin. This is very unfair. The Old English form of the word was riht.

Thanks to J Alan Smith for his permission to use his letter. A longer piece by J Alan Smith on this topic can be found HERE. It's worth a look.

It's about labels - and how they so often end up stuck over the flipping bar code.

SIR - The political affection for the "centre ground" and the disdain for "extremes", the "far-Right" and - very occasionally - the "far-Left" rest on the assumption that each of us can be represented by points on a line according to our political views.

Suppose that this is not true. We should have to replace the "centre ground" with the more useful "common ground" and, instead of debating whether proposals were of the Right or Left, debate whether the were right or wrong.

J Alan Smith

Epping, Essex

How about that? Sorts out the world in three sentences!

Word To Us Today: right. Both the main meanings of this word, correct and the opposite of left, have the same origin. This is very unfair. The Old English form of the word was riht.

Thanks to J Alan Smith for his permission to use his letter. A longer piece by J Alan Smith on this topic can be found HERE. It's worth a look.

Wednesday, 13 March 2019

Nuts and Bolts: ATOS.

When I was very young I used to work out which books were easy enough for me by the size of the print.

Nowadays, however, things are different, because we now have ATOS. ATOS is a computer program which can analyse the text of a passage or whole book and assign it a difficulty number.

It's very important to note that the ATOS analysis doesn't take into account what the text is about, or how long it is, and therefore it tells you nothing about anything sophisticated, like a book's theme. What it does tell you is how difficult it is on average to read the words and understand a sentence.

Some of the results are surprising. Roger Hargreaves' wonderful little book for infants Mr Greedy, for instance, is measured to be a book of the same level of difficulty as Malorie Blackman's teenager Noughts and Crosses books, and only a little easier than John Steinbeck's decidedly adult The Grapes of Wrath.

Yes, yes, this result is basically nonsense, but it's interesting to know that simplicity and directness of language isn't any barrier to communicating complex, sophisticated, vivid, and wise stories.

But then I suppose we always knew that long sentences and long words are often a means of disguising a fundamental lack of sense, didn't we.

You can measure the ATOS difficulty of any text HERE.

Word To Use Today: how about a short one in a short sentence? I think, so I am will do.

By the way, the two hardest books, as measured by the ATOS formula, are Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift and Don Quixote* by Miguel de Cervantes, both of which I've rewritten for Oxford Children's Books.

I feel really rather proud of that.

*I don't know if this was measured in the original Spanish version or one in English.

Nowadays, however, things are different, because we now have ATOS. ATOS is a computer program which can analyse the text of a passage or whole book and assign it a difficulty number.

It's very important to note that the ATOS analysis doesn't take into account what the text is about, or how long it is, and therefore it tells you nothing about anything sophisticated, like a book's theme. What it does tell you is how difficult it is on average to read the words and understand a sentence.

Some of the results are surprising. Roger Hargreaves' wonderful little book for infants Mr Greedy, for instance, is measured to be a book of the same level of difficulty as Malorie Blackman's teenager Noughts and Crosses books, and only a little easier than John Steinbeck's decidedly adult The Grapes of Wrath.

Yes, yes, this result is basically nonsense, but it's interesting to know that simplicity and directness of language isn't any barrier to communicating complex, sophisticated, vivid, and wise stories.

But then I suppose we always knew that long sentences and long words are often a means of disguising a fundamental lack of sense, didn't we.

You can measure the ATOS difficulty of any text HERE.

Word To Use Today: how about a short one in a short sentence? I think, so I am will do.

By the way, the two hardest books, as measured by the ATOS formula, are Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift and Don Quixote* by Miguel de Cervantes, both of which I've rewritten for Oxford Children's Books.

I feel really rather proud of that.

*I don't know if this was measured in the original Spanish version or one in English.

Tuesday, 12 March 2019

Thing Not To Be Today: old.

It's not a matter of how long you've been alive, they say, it's how you feel...

...and anyone who remembers the triple-gravity gum-eyed drag of being an awakening teenager with only double Geography to look forward to will understand this well.

Now there are, of course, plenty of sprightly oldsters who insist on running chirpy marathons when they should have long ago learned better, but for the rest of us: how do we stop getting old?

Three suggestions:

Be properly interested in other people (this involves listening!).

Keep an open mind.

Bear in mind the history of the word old, and do your best to live up to it.

There we are.

Not quite eternal youth, but as close as most of us are going to get.

beautiful lady from Darap village, Sikkim. Photo: Sukanto Debnath.

Thing Not To Be Today: old. This word comes from the Old English eald and is related to the Latin altus, high.

...and anyone who remembers the triple-gravity gum-eyed drag of being an awakening teenager with only double Geography to look forward to will understand this well.

Now there are, of course, plenty of sprightly oldsters who insist on running chirpy marathons when they should have long ago learned better, but for the rest of us: how do we stop getting old?

Three suggestions:

Be properly interested in other people (this involves listening!).

Keep an open mind.

Bear in mind the history of the word old, and do your best to live up to it.

There we are.

Not quite eternal youth, but as close as most of us are going to get.

beautiful lady from Darap village, Sikkim. Photo: Sukanto Debnath.

Thing Not To Be Today: old. This word comes from the Old English eald and is related to the Latin altus, high.