To be in cahoots with someone is to be plotting with him or her, but the resultant scheme is unlikely to lead to anything cruel or deadly. The word cahoots itself, obviously, cannot be taken seriously; and neither, frankly, can the plotters.

You and your accomplices might have a grand plan to corner the market in paper clips, but the implications of being in cahoots are that you'll do it so incompetently that the bottom lines of the other paper clip distributers will barely wobble.

Villains who are in cahoots are stupid, buffoonish - and probably obvious.

Hmm...

It occurs to me that, given the current state of world affairs, it is no surprise at all that the phrase is in my mind.

Thing Not To Be Today: in cahoots. There are two theories about the origin of this word. It might come from the French cahute, which means cabin, or it might comes from the French cohort, which in English has been used as a slang word for accomplice.

I rather fancy the cahute origin, as it has the right kind of rustic feel to it.

Tuesday, 30 April 2019

Monday, 29 April 2019

Spot the Frippet: oleograph.

There are two kinds of oleograph.

One is a picture printed in oil paint to give the impression of an oil painting:

Love or Duty by Gabriele Castagnola 1873. Hideous, isn't it.

Love or Duty by Gabriele Castagnola 1873. Hideous, isn't it.

Each colour has to be printed separately, and the shading done by stippling, and this means the whole process both expensive and slow.

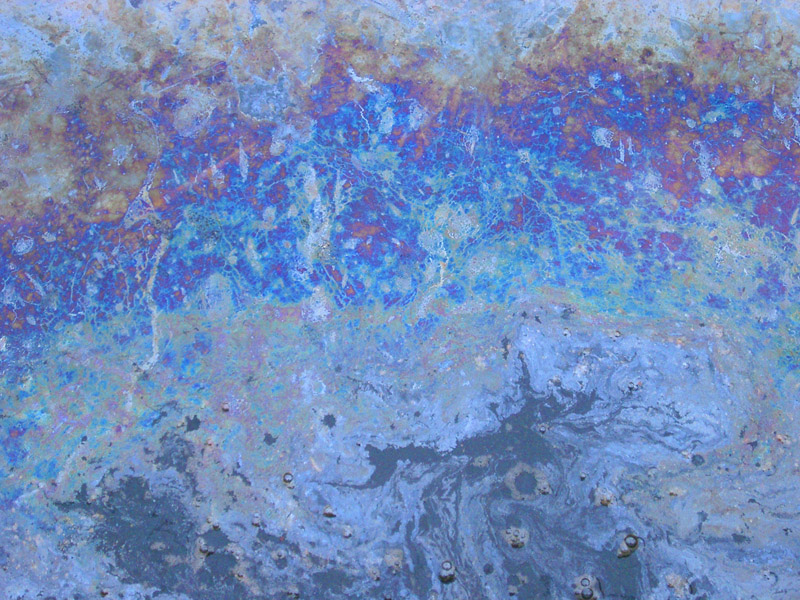

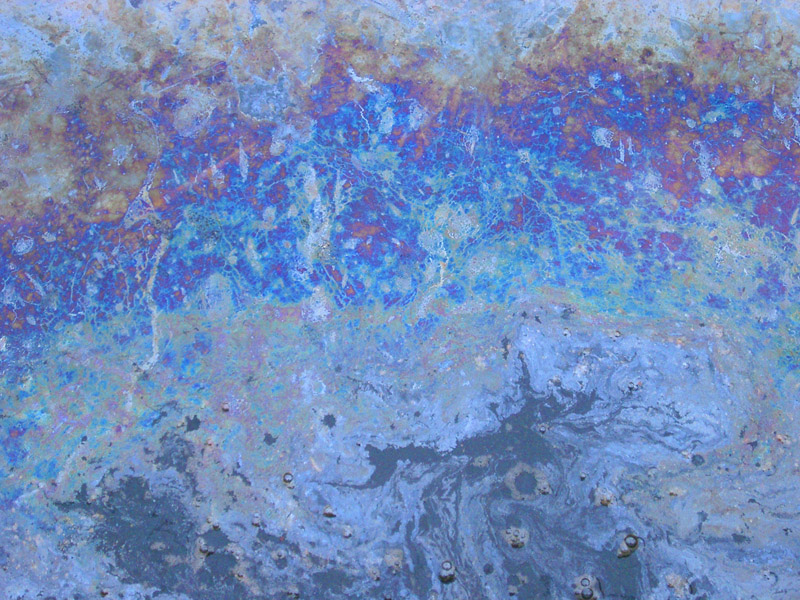

These pictures are also sometimes called chromolithographs, and I admit you aren't very likely to come across one, but luckily the other sort of oleograph is both very beautiful and can be found all over the place, because it's the pattern made when a drop of oil is seen floating on water.

It's most usually petrol:

oil on the River Deule, France. Photo by Lamiot

photo by Creativity103

It's always beautiful, though admittedly nearly always a disaster.

A drop of oil in a bowl of water will give you a DIY version, or the marbled endpapers of books work on the same principle.

Spot the Frippet: an oleograph. The Latin word oleum means oil, and the Greek word graphein is to do with writing.

One is a picture printed in oil paint to give the impression of an oil painting:

Love or Duty by Gabriele Castagnola 1873. Hideous, isn't it.

Love or Duty by Gabriele Castagnola 1873. Hideous, isn't it.Each colour has to be printed separately, and the shading done by stippling, and this means the whole process both expensive and slow.

These pictures are also sometimes called chromolithographs, and I admit you aren't very likely to come across one, but luckily the other sort of oleograph is both very beautiful and can be found all over the place, because it's the pattern made when a drop of oil is seen floating on water.

It's most usually petrol:

oil on the River Deule, France. Photo by Lamiot

photo by Creativity103

It's always beautiful, though admittedly nearly always a disaster.

A drop of oil in a bowl of water will give you a DIY version, or the marbled endpapers of books work on the same principle.

Spot the Frippet: an oleograph. The Latin word oleum means oil, and the Greek word graphein is to do with writing.

Sunday, 28 April 2019

Sunday Rest: grumous. Word Not To Use Today.

Do not use the word grumous.

Just don't, okay?

For one reason, no one will understand it, and, for another, it sounds like something that gives you chronic stomach-ache (and, as a matter of fact, it sometimes is).

But there's yet another reason not to use this word, and it is by far the most important, and that is that you don't understand it, either.

Just imagine a world where we only used words we understood.

It would be a lot quieter and more peaceful, wouldn't it.

Word Not To Use Today: grumous. This word is usually used of plants and in anatomy. In plants it describes something with a granular texture, like the roots of some plants. In anatomy it often describes the reaction of the body to a wound. The word comes from the grume, a clot of blood, from the Latin grumus, a little heap. Grumous can also be used to describe something with a porridge-like texture, like...er...porridge.

But that would put people off their breakfast, so I wouldn't.

Just don't, okay?

For one reason, no one will understand it, and, for another, it sounds like something that gives you chronic stomach-ache (and, as a matter of fact, it sometimes is).

But there's yet another reason not to use this word, and it is by far the most important, and that is that you don't understand it, either.

Just imagine a world where we only used words we understood.

It would be a lot quieter and more peaceful, wouldn't it.

Word Not To Use Today: grumous. This word is usually used of plants and in anatomy. In plants it describes something with a granular texture, like the roots of some plants. In anatomy it often describes the reaction of the body to a wound. The word comes from the grume, a clot of blood, from the Latin grumus, a little heap. Grumous can also be used to describe something with a porridge-like texture, like...er...porridge.

But that would put people off their breakfast, so I wouldn't.

Saturday, 27 April 2019

Saturday Rave: The Owl and The Nightingale. Anon.

It's Spring here in England, and the birds are singing.

Well, the ducks aren't singing - nor the crows - nor the owls. But you know what I mean.

Here's a very old poem on that very theme, The Owl and the Nightingale. It might have been written as early as 1189, but even so the language it uses can just about be recognised as English.

The whole thing is very long, and it's basically an argument between the eponymous owl and nightingale, who disagree about...well, everything, pretty much. There are a lot of insults (I'd rather spit than sing about your wretched howling) but in the end...well, I'm afraid there isn't an end. We leave them setting off to take their dispute to a court of law.

Here's the very beginning, with a modern English version after it.

Well, the ducks aren't singing - nor the crows - nor the owls. But you know what I mean.

Here's a very old poem on that very theme, The Owl and the Nightingale. It might have been written as early as 1189, but even so the language it uses can just about be recognised as English.

The whole thing is very long, and it's basically an argument between the eponymous owl and nightingale, who disagree about...well, everything, pretty much. There are a lot of insults (I'd rather spit than sing about your wretched howling) but in the end...well, I'm afraid there isn't an end. We leave them setting off to take their dispute to a court of law.

Here's the very beginning, with a modern English version after it.

Ich was in one sumere dale,

in one suþe diȝele hale,

iherde ich holde grete tale

an hule and one niȝtingale.

Þat plait was stif & starc & strong,

sum wile softe & lud among;

an aiþer aȝen oþer sval,

& let þat [vue]le mod ut al

& eiþer seide of oþeres custe

þat alre-worste þat hi wuste:

& hure & hure of oþere[s] songe

hi holde plaiding suþe stronge.

***

***

I was in a springtime valley

in a very sheltered glade.

I heard a great argument between

an owl and a nightingale.

The debate was stiff and fierce and strong

sometimes soft and sometimes loud

and each of them raged

and burst to curse the other

saying the very worst she could

about the other's character

and especially they quarrelled fiercely

about each other's song.

****

Well, at least they were both did their singing at night.

Imagine how annoying they both were to everyone who

was trying to get some sleep!

was trying to get some sleep!

Word To Use Today: owl. The Old English form

of this word was ūle.

Friday, 26 April 2019

Word To Use Today: bludger.

Yes, a bludger really has got something to do with a bludgeon, but it doesn't actually involve hitting anyone.

A bludger, in Australia and New Zealand, is a scrounger, or someone work-shy, or someone who is supposed to be in authority but is ignored by his or her inferiors.

There's a verb, too, to bludge, which has the same sorts of meanings, but is also means to have a very easy and undemanding job.

What's the connection?

This.

Word To Use Today: bludger. A bludgeon is a club (the word appeared in the 1700s, but no one knows from where) and the verb to bludgeon means to hit someone with such a weapon. It also means to bully or coerce someone, as in she bludgeoned him into standing for election. From there, in Australia and New Zealand, this became shortened to bludge, and it then extended its meaning to include a person who ran a business hiring out women as slaves to men. From there it came to mean a scrounger, and hence acquired all its other meanings.

A bludger, in Australia and New Zealand, is a scrounger, or someone work-shy, or someone who is supposed to be in authority but is ignored by his or her inferiors.

There's a verb, too, to bludge, which has the same sorts of meanings, but is also means to have a very easy and undemanding job.

What's the connection?

This.

Word To Use Today: bludger. A bludgeon is a club (the word appeared in the 1700s, but no one knows from where) and the verb to bludgeon means to hit someone with such a weapon. It also means to bully or coerce someone, as in she bludgeoned him into standing for election. From there, in Australia and New Zealand, this became shortened to bludge, and it then extended its meaning to include a person who ran a business hiring out women as slaves to men. From there it came to mean a scrounger, and hence acquired all its other meanings.

Thursday, 25 April 2019

The female of the species: a rant.

Kiju Jung is the lead-author of a study which tells us that hurricanes given female names cause more fatalities than those given male names.

The basic idea is that because women aren't conceived as being as strong and intense as men, hurricanes with female names don't seem as scary and so people don't run away and hide as fast. Or, indeed, at all.

The study involved ranking the storm names from very feminine to very masculine (which is odd in itself, because I'd have said that generally names are one or the other).

"People imagining a 'female' hurricane were not as willing to seek shelter," said co-author Sharon Shavit. "The stereotypes that underlie these judgments are subtle and not necessarily hostile toward women - they may involve viewing women as warmer and less aggressive than men."

I'd like to draw attention to two points, here. First, the use of the word imagining. This word is necessarily present because the results of the study were partly based on a questionnaire, not on actual hurricane data.

Second, it's worth looking at the authors of the study. The lead author Kiju Jung is a doctoral student, and his co-authors Madhu Viswanathan and Sharon Shavitt are both professors from the University of Illinois (there's another author, Joseph Hilbe, of Arizona Sate University, but I don't know anything about him).

And are these people meteorologists? Statisticians?

Nope.

They are specialists in...

...marketing.

From this evidence, they are rather good at it, too.

Word To Use Today: hurricane. This word comes from Spanish, from the Taino word hura, which means wind.

The basic idea is that because women aren't conceived as being as strong and intense as men, hurricanes with female names don't seem as scary and so people don't run away and hide as fast. Or, indeed, at all.

The study involved ranking the storm names from very feminine to very masculine (which is odd in itself, because I'd have said that generally names are one or the other).

"People imagining a 'female' hurricane were not as willing to seek shelter," said co-author Sharon Shavit. "The stereotypes that underlie these judgments are subtle and not necessarily hostile toward women - they may involve viewing women as warmer and less aggressive than men."

I'd like to draw attention to two points, here. First, the use of the word imagining. This word is necessarily present because the results of the study were partly based on a questionnaire, not on actual hurricane data.

Second, it's worth looking at the authors of the study. The lead author Kiju Jung is a doctoral student, and his co-authors Madhu Viswanathan and Sharon Shavitt are both professors from the University of Illinois (there's another author, Joseph Hilbe, of Arizona Sate University, but I don't know anything about him).

And are these people meteorologists? Statisticians?

Nope.

They are specialists in...

...marketing.

From this evidence, they are rather good at it, too.

Word To Use Today: hurricane. This word comes from Spanish, from the Taino word hura, which means wind.

Wednesday, 24 April 2019

Nuts and Bolts: Historical Colour.

We can make colour photographs nowadays at the click of a phone, but what could you do if you wanted to describe a colour in the 1500s?

Well, you had to be creative.

This means that in those days there were fabrics glorying in the delightful shades of rat's colour and puke (dull grey and dirty brown, respectively. Worn by poor people), not to mention gooseturd green and dead Spaniard (a pale greyish tan).

If you were rich enough you might wear popingay green, which was a sort of turquoise (though turquoise is rather unusual for popingays, which we nowadays tend to call parrots). You might wear a light blue called plunket, or a pale greenish blue called watchet, combined perhaps with buff-cloured Isabella and red strammel.

Queen Mary Tudor loved crane (a greyish white) and old medley (sorry, no idea). Presumably Queen Mary was not so keen on mortal sin, though her half-sister Elizabeth, one feels, would have appreciated lustie-gallant, which was a light red, or the now unknown colouring of kiss me darling.

And what colour might croyde, mostyns, and friar colour be? What shade exactly is long fine blue? Or sad new colour? How about biscaye? Or devil in the head? What could scratch-face or ape's laugh look like? Or flybert?

Sadly, no one is sure about any of these nowadays.

So: are we better off with our colour photographs?

Well, yes, we are, though I do mourn the loss of colour names like celestial.

But, I don't know...I have just adorn my kitchen wall with a paint colour called Mind Your Own Beeswax (it's egg yolk yellow).

And it's pleasing to know that bonkers creativity still lives.

Word To Use Today: a colour word. The origin of the word magenta, for instance, is interesting.

Well, you had to be creative.

This means that in those days there were fabrics glorying in the delightful shades of rat's colour and puke (dull grey and dirty brown, respectively. Worn by poor people), not to mention gooseturd green and dead Spaniard (a pale greyish tan).

If you were rich enough you might wear popingay green, which was a sort of turquoise (though turquoise is rather unusual for popingays, which we nowadays tend to call parrots). You might wear a light blue called plunket, or a pale greenish blue called watchet, combined perhaps with buff-cloured Isabella and red strammel.

Queen Mary Tudor loved crane (a greyish white) and old medley (sorry, no idea). Presumably Queen Mary was not so keen on mortal sin, though her half-sister Elizabeth, one feels, would have appreciated lustie-gallant, which was a light red, or the now unknown colouring of kiss me darling.

And what colour might croyde, mostyns, and friar colour be? What shade exactly is long fine blue? Or sad new colour? How about biscaye? Or devil in the head? What could scratch-face or ape's laugh look like? Or flybert?

Sadly, no one is sure about any of these nowadays.

So: are we better off with our colour photographs?

Well, yes, we are, though I do mourn the loss of colour names like celestial.

But, I don't know...I have just adorn my kitchen wall with a paint colour called Mind Your Own Beeswax (it's egg yolk yellow).

And it's pleasing to know that bonkers creativity still lives.

Word To Use Today: a colour word. The origin of the word magenta, for instance, is interesting.

Tuesday, 23 April 2019

Thing To Be Today: fond.

'I am a very foolish fond old man' says King Lear, heartbreakingly, and although he is talking to his very dear daughter he is not speaking of his affection for her, for to Lear to be fond was to be stupid and easily deceived.

There's still a trace of this meaning in the expression fond hopes: these may be hopes for which we have an affection, but the main idea is that these hopes are unrealistic or even foolish, as in:

I have fond hopes that Millwall will win the FA Cup in my lifetime.

Nowadays the usual meaning of fond is, of course, to feel liking, love or tenderness for someone or something. Even this might have a touch of foolishness, though: a fond mother is quite likely to be blindly over-indulgent. But then, as another literary William* tells us, Love makes fools of us all, big and little, and so sadly all we can do is live in solitary bitterness or allow ourselves to be fond in both senses.

I know what I'm going to choose.

Thing To Be Today: fond. This word comes from the Middle English word fonne, a fool.

*Thackeray.

There's still a trace of this meaning in the expression fond hopes: these may be hopes for which we have an affection, but the main idea is that these hopes are unrealistic or even foolish, as in:

I have fond hopes that Millwall will win the FA Cup in my lifetime.

Nowadays the usual meaning of fond is, of course, to feel liking, love or tenderness for someone or something. Even this might have a touch of foolishness, though: a fond mother is quite likely to be blindly over-indulgent. But then, as another literary William* tells us, Love makes fools of us all, big and little, and so sadly all we can do is live in solitary bitterness or allow ourselves to be fond in both senses.

I know what I'm going to choose.

Thing To Be Today: fond. This word comes from the Middle English word fonne, a fool.

*Thackeray.

Monday, 22 April 2019

Spot the Frippet: omelette.

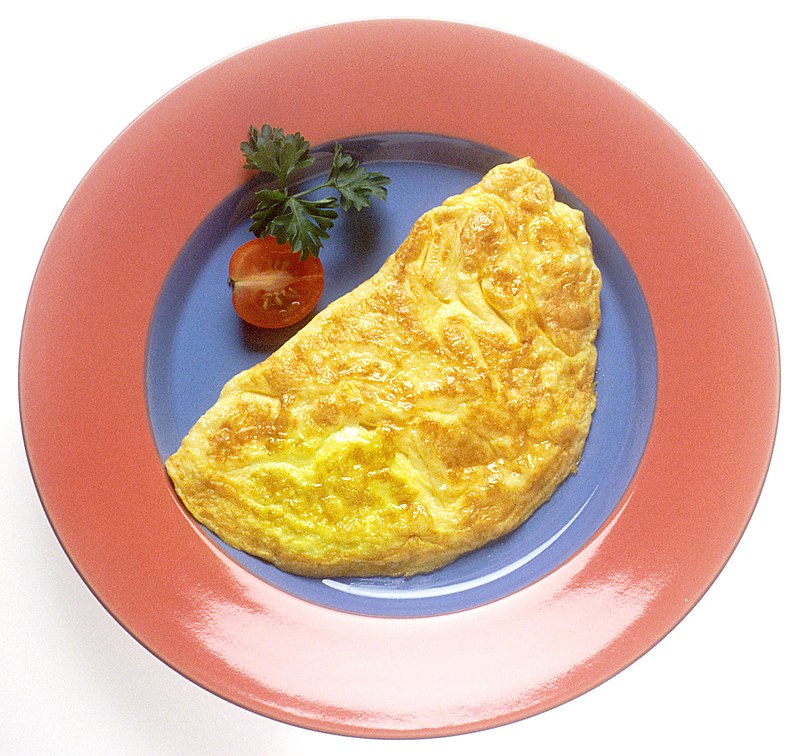

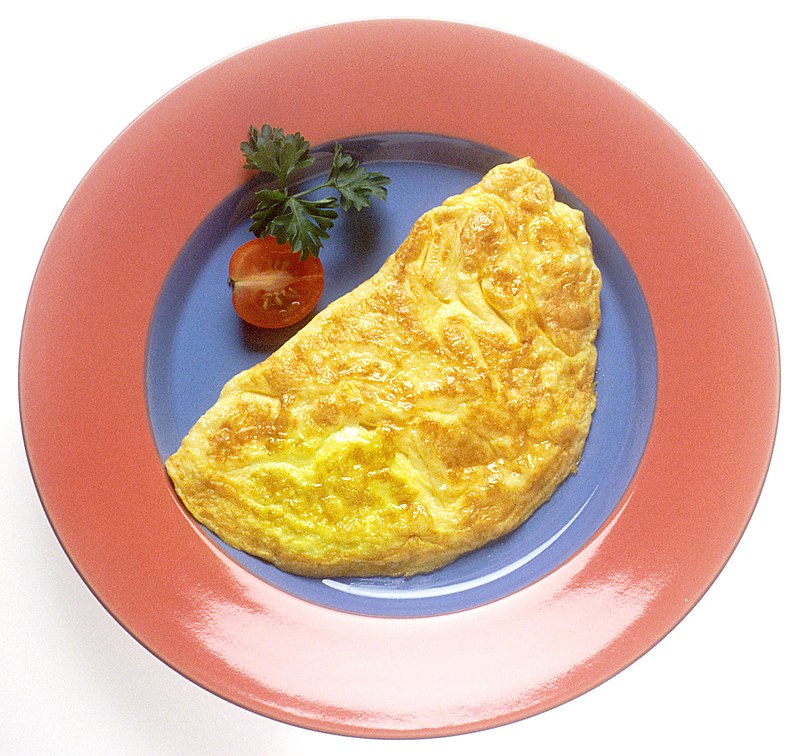

You can't make an omelette without breaking eggs, or so they say (though actually you can, because these vegans get everywhere with their chick peas and their tofu, don't they).

I have to agree that omelettes are seldom spotted coming along the road, but if you don't happen to come across an omelette as you go about your business then it's easy enough to make one. (I've always found that the very best ones have mushrooms in them.)

Actually, though, the real reason for this post is the particularly peculiar history of the word.

Spot the Frippet: omelette. This word came into the English language in the 1600s from France. Before it was called an omelette the French called the thing an allumette, which means sword blade - which is, obviously, nothing like an omelette:

- but this is because the French had split up the words la lemelle wrongly by mistake and somehow ended up with allumette. (We've done quite a lot of that sort of thing in English, too: for example the thing you wear to make an omelette used to be called a napron.) Lemelle comes from the Latin lamella, from lāmina, a thin plate.

I have to agree that omelettes are seldom spotted coming along the road, but if you don't happen to come across an omelette as you go about your business then it's easy enough to make one. (I've always found that the very best ones have mushrooms in them.)

Actually, though, the real reason for this post is the particularly peculiar history of the word.

Spot the Frippet: omelette. This word came into the English language in the 1600s from France. Before it was called an omelette the French called the thing an allumette, which means sword blade - which is, obviously, nothing like an omelette:

*can you spot the difference?*

- but this is because the French had split up the words la lemelle wrongly by mistake and somehow ended up with allumette. (We've done quite a lot of that sort of thing in English, too: for example the thing you wear to make an omelette used to be called a napron.) Lemelle comes from the Latin lamella, from lāmina, a thin plate.

Sunday, 21 April 2019

Sunday Rest: garbo. Word Not To Use Today.

All words are dangerous, but some are more dangerous than others.

For instance, to call a lady a garbo in most parts of the world is to imply that she is beautiful, formidable, and enigmatic.

Greta Garbo. Photo by Ruth Harriet Louise. Publicity shot for Wild Orchids, 1929.

If you're in Australia, or talking to an Australian, however, you'd be calling her a refuse collector.

Like I say, dangerous.

Word Not To Use Today: garbo. Greta Garbo's surname was originally Gustafsson. Garbo, as in refuse collector, is to do with the word garbage. Where the word garbage comes from isn't known, but there's a lovely Old Italian word garbulio, which means confusion, which might have something to do with it.

For instance, to call a lady a garbo in most parts of the world is to imply that she is beautiful, formidable, and enigmatic.

Greta Garbo. Photo by Ruth Harriet Louise. Publicity shot for Wild Orchids, 1929.

If you're in Australia, or talking to an Australian, however, you'd be calling her a refuse collector.

Like I say, dangerous.

Word Not To Use Today: garbo. Greta Garbo's surname was originally Gustafsson. Garbo, as in refuse collector, is to do with the word garbage. Where the word garbage comes from isn't known, but there's a lovely Old Italian word garbulio, which means confusion, which might have something to do with it.

Saturday, 20 April 2019

Saturday Rave: A Very Short Song by Dorothy Parker.

Dorothy Parker is most famous for her New York wit. This annoyed her, rather (though it made her some fast friends and helped to earn her a living) because her main work was writing reviews, plays, short stories, screen plays, essays and poems.

Here she is:

and here is one of her poems.

It's wonderful.

Once, when I was young and true,

Someone left me sad -

Broke my brittle heart in two,

And that is very bad.

Love is for unlucky folk,

Love is but a curse.

Once there was a heart I broke:

And that, I think, is worse.

Dorothy Parker died at the age of seventy three.

She left her estate to Martin Luther King Jr.

Her ashes remained unclaimed for seventeen years.

Word To Use Today: true. This word true was triewe in Old English. It's related to the Old High German truwi, loyal, and the English word trust.

Here she is:

and here is one of her poems.

It's wonderful.

Once, when I was young and true,

Someone left me sad -

Broke my brittle heart in two,

And that is very bad.

Love is for unlucky folk,

Love is but a curse.

Once there was a heart I broke:

And that, I think, is worse.

Dorothy Parker died at the age of seventy three.

She left her estate to Martin Luther King Jr.

Her ashes remained unclaimed for seventeen years.

Word To Use Today: true. This word true was triewe in Old English. It's related to the Old High German truwi, loyal, and the English word trust.

Friday, 19 April 2019

Word To Use Today: inchmeal.

Inchmeal might sound like flaked caterpillar food, but it isn't.

The inch in inchmeal is the same sort of thing as in the US English inchworm:

photo by Katja Schultz https://www.flickr.com/people/86548370@N00

- that is, a unit of measurement more or less equivalent to two and a half centimetres, or the width of the human thumb (ooh, I've just measured mine, and I have rather slender thumbs) - but the meal bit isn't to do with flakes of grain designed for food use.

No, it's the sort of meal we're supposed to eat three times a day.

Basically, inchmeal is the same sort of word as piecemeal, but instead of something being made or achieved or destroyed piece by piece it happens, yes, inch by inch (an inch being a very small amount).

Ah well. It may be slow, but at least inchmeal means that things are moving in the right direction.

Unless, I suppose, it's the wrong one.

Word To Use Today: inchmeal. The word inch comes from the Old English ynce from the Latin uncia which means a twelfth (though when do you ever see twelve thumbs lined up together? Well, I suppose it might be a good game for breaking the ice at a party). Meal comes from the Old English mælum, a quantity taken at one time.

The English word "inch" (Old English: ynce) was an early borrowing from Latin uncia ("one-twelfth; Roman inch; Roman ounce") not present in other Germanic languages.[1] The vowel change from Latin /u/ to Old English /y/ (which became Modern English /ɪ/) is known as umlaut.

The inch in inchmeal is the same sort of thing as in the US English inchworm:

photo by Katja Schultz https://www.flickr.com/people/86548370@N00

- that is, a unit of measurement more or less equivalent to two and a half centimetres, or the width of the human thumb (ooh, I've just measured mine, and I have rather slender thumbs) - but the meal bit isn't to do with flakes of grain designed for food use.

No, it's the sort of meal we're supposed to eat three times a day.

Basically, inchmeal is the same sort of word as piecemeal, but instead of something being made or achieved or destroyed piece by piece it happens, yes, inch by inch (an inch being a very small amount).

Ah well. It may be slow, but at least inchmeal means that things are moving in the right direction.

Unless, I suppose, it's the wrong one.

Word To Use Today: inchmeal. The word inch comes from the Old English ynce from the Latin uncia which means a twelfth (though when do you ever see twelve thumbs lined up together? Well, I suppose it might be a good game for breaking the ice at a party). Meal comes from the Old English mælum, a quantity taken at one time.

The English word "inch" (Old English: ynce) was an early borrowing from Latin uncia ("one-twelfth; Roman inch; Roman ounce") not present in other Germanic languages.[1] The vowel change from Latin /u/ to Old English /y/ (which became Modern English /ɪ/) is known as umlaut.

Thursday, 18 April 2019

The chemistry of Judi Dench: a rant.

There is nothing like a dame, or so the song says, and Dame Judi Dench has long been one of the wonders of the world: a very good actress, and by all accounts a very good companion, too, with a deeply impressive habit of learning some poetry every day.

Dame Judi can be equally convincing as a queen (Shakespeare in Love, 1998, Mrs Brown, 1997), a philosopher (Iris, 2001), a teacher (Notes on a Scandal, 2006) and a cynical critic (Rage, 2009).

But there are things even beyond the range of Dame Judi, and I doubt she could come even close to...well, this claim, below, which was made in the Telegraph online newspaper.

So infinitesimally nuanced is the acting of this star alum of the Royal Shakespeare Company that it only took an eight-minute turn as Queen Elizabeth I in Shakespeare in Love (1998) to win her an Oscar.

An alum? A star alum? As in, the colourless hydrated sulphate of aluminium and potassium used for setting dyes, treating leather and paper, and to stop bleeding?

Or does that mean, more loosely, any isomorphic double sulphate of a monovalent metal and a trivalent metal, formula:

X₂SO₄.Y₂(SO₄)₃.24H₂O

where X is monovalent and Y is trivalent?

Or, on the other hand, is it just that the writer was in terror of the female ending of the word alumna and has been panicked into nonsense?

I know what I think.

Word To Use Today: alumna. This is from the Latin word alere to nourish, and means nurseling or foster daughter or pupil.

Dame Judi can be equally convincing as a queen (Shakespeare in Love, 1998, Mrs Brown, 1997), a philosopher (Iris, 2001), a teacher (Notes on a Scandal, 2006) and a cynical critic (Rage, 2009).

But there are things even beyond the range of Dame Judi, and I doubt she could come even close to...well, this claim, below, which was made in the Telegraph online newspaper.

So infinitesimally nuanced is the acting of this star alum of the Royal Shakespeare Company that it only took an eight-minute turn as Queen Elizabeth I in Shakespeare in Love (1998) to win her an Oscar.

An alum? A star alum? As in, the colourless hydrated sulphate of aluminium and potassium used for setting dyes, treating leather and paper, and to stop bleeding?

Or does that mean, more loosely, any isomorphic double sulphate of a monovalent metal and a trivalent metal, formula:

X₂SO₄.Y₂(SO₄)₃.24H₂O

where X is monovalent and Y is trivalent?

Or, on the other hand, is it just that the writer was in terror of the female ending of the word alumna and has been panicked into nonsense?

I know what I think.

Word To Use Today: alumna. This is from the Latin word alere to nourish, and means nurseling or foster daughter or pupil.

Wednesday, 17 April 2019

Nuts and Bolts: obelus.

There are two types of obeluses, and three ways of writing one.

You've come across them all already. One is the dagger symbol which either acts like an asterisk to draw attention to a footnote or means that the person with the obelus next to to his name has, sadly, snuffed it.

It looks like this:

†

The other sort of obelus you know as well, because it looks either like this:

÷

which usually means divided by (although some Scandinavians used it to mean subtracted by until fairly recently, and in Italy it sometimes indicates a range of values) but can also be used to mark a passage of a book that's reckoned not to be authentic. This kind of obelus can also look like this:

-

The plural of obelus can be either obeluses or the delightful obeli, so this means that if an extremely ancient and frail scholar has been marking up a book for suspect passages there's always a chance that he or she will do it using wobbly obeli.

One can but hope, anyway.

Word To Use Today: obelus. This word comes from the Greek obelos, which means sharpened stick, spit or pointed pillar. It's basically the same word as obelisk.

You've come across them all already. One is the dagger symbol which either acts like an asterisk to draw attention to a footnote or means that the person with the obelus next to to his name has, sadly, snuffed it.

It looks like this:

†

The other sort of obelus you know as well, because it looks either like this:

÷

which usually means divided by (although some Scandinavians used it to mean subtracted by until fairly recently, and in Italy it sometimes indicates a range of values) but can also be used to mark a passage of a book that's reckoned not to be authentic. This kind of obelus can also look like this:

-

The plural of obelus can be either obeluses or the delightful obeli, so this means that if an extremely ancient and frail scholar has been marking up a book for suspect passages there's always a chance that he or she will do it using wobbly obeli.

One can but hope, anyway.

Word To Use Today: obelus. This word comes from the Greek obelos, which means sharpened stick, spit or pointed pillar. It's basically the same word as obelisk.

Tuesday, 16 April 2019

Thing To Be Yesterday: egregious.

If someone is egregious he or she is outstandingly bad, flagrantly awful, completely terrible.

(I'm sure there is no need to provide illustrative examples.)

But, you know something? Just look at the origin of the word!

Thing To Be Yesterday: egregious. This word appeared in English in the 1530s, when it meant distinguished, excellent or eminent. It comes from the Latin ēgregius, which means the same sort of thing. Ēgregius comes from ex grege, rising above the flock, from grex, a herd or flock.

So why does it now mean exactly the opposite?

Well, because someone in the late 1500s got sarcastic, and the sarcasm caught on so completely that the original meaning has withered away.

Wouldn't it be well wicked if it got swopped back again?

(I'm sure there is no need to provide illustrative examples.)

But, you know something? Just look at the origin of the word!

Thing To Be Yesterday: egregious. This word appeared in English in the 1530s, when it meant distinguished, excellent or eminent. It comes from the Latin ēgregius, which means the same sort of thing. Ēgregius comes from ex grege, rising above the flock, from grex, a herd or flock.

So why does it now mean exactly the opposite?

Well, because someone in the late 1500s got sarcastic, and the sarcasm caught on so completely that the original meaning has withered away.

Wouldn't it be well wicked if it got swopped back again?

Monday, 15 April 2019

Spot the Frippet: drake.

The easiest kind of drake to spot here in England is a male duck, and the easiest of those in my town is a mallard drake. His malachite head shines marvellously in the sun:

photo by Acarpentier

- though unfortunately spotting any sun to make it shine is rather harder.

There are many other kinds of drake:

harlequin drake, photo by Peter Massas

mandarin drake, photo by Seahamlass

and they're not all birds.

A mandrake is a plant with a forked and magic (or so they say) root:

it's native to Europe and the Middle East. It has pretty flowers (photo: tato grasso):

but it's poisonous and can cause hallucinations, unconsciousness, and death.

A fisherman's drake is a fly tied to resemble a mayfly:

green drake, photo by Mike Cline

a soldier's drake is a small cannon; and of course a drake is another word for dragon:

Sydney half-sovereign, designed by Benedetto Pistrucci

And dragons are always worth looking out for, just in case.

Spot the Frippet: drake. The bird word appeared in English in the 1200s, probably from Low German. The dragon/cannon/fly word comes from the Old English draca, from the Latin dracō, dragon.

The mandrake got its name from the Latin word mandragora, which first of all the French turned into main de gloire, and then the English changed further into mandrake, on the grounds that it looks a bit like a man, and it's sort of magical, like a dragon.

photo by Acarpentier

- though unfortunately spotting any sun to make it shine is rather harder.

There are many other kinds of drake:

harlequin drake, photo by Peter Massas

mandarin drake, photo by Seahamlass

and they're not all birds.

A mandrake is a plant with a forked and magic (or so they say) root:

it's native to Europe and the Middle East. It has pretty flowers (photo: tato grasso):

but it's poisonous and can cause hallucinations, unconsciousness, and death.

A fisherman's drake is a fly tied to resemble a mayfly:

green drake, photo by Mike Cline

a soldier's drake is a small cannon; and of course a drake is another word for dragon:

Sydney half-sovereign, designed by Benedetto Pistrucci

And dragons are always worth looking out for, just in case.

Spot the Frippet: drake. The bird word appeared in English in the 1200s, probably from Low German. The dragon/cannon/fly word comes from the Old English draca, from the Latin dracō, dragon.

The mandrake got its name from the Latin word mandragora, which first of all the French turned into main de gloire, and then the English changed further into mandrake, on the grounds that it looks a bit like a man, and it's sort of magical, like a dragon.